These days, organizations want to make sure they’re getting publicity for the right reasons, not for their ethical lapses. Just ask Volkswagen and Uber. Volkswagen was caught lying to customers and regulators about the performance of its diesel engines, even going so far as to program its cars to give misleading emissions information. In 2017, details emerged about Uber’s Project Greyball, a systematic, coordinated effort to evade law enforcement officials where the ride-hailing service was banned.

To makes sure you don’t end up in the same boat at Volkswagen and Uber, your organization needs to adopt guidelines that promote ethical decision making, and make ethics a priority for all employees. Here are three frameworks for ethical decision making.

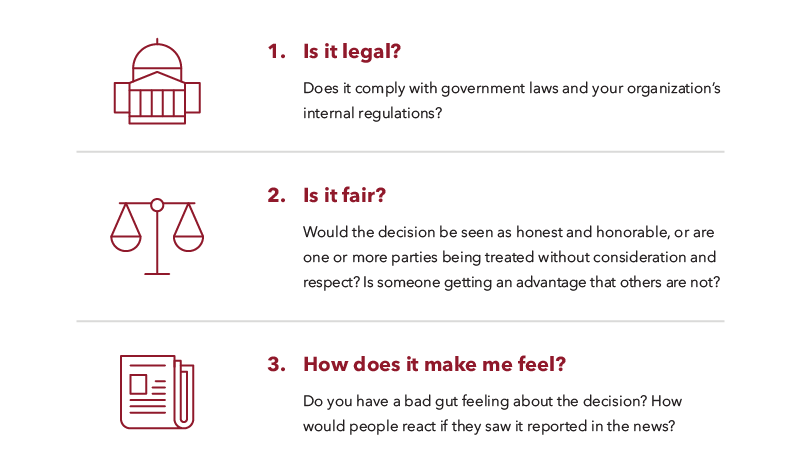

The Blanchard-Peale Framework

One of the best-known ethical frameworks is also one of the simplest. The framework developed by Ken Blanchard and Norman Vincent Peale consists of three questions, as described below. The questions first appeared in their 1988 book, “The Power of Ethical Management.”

Markkula Center Framework

The Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University identifies five approaches, or dimensions, that can be applied when dealing with an ethical issue. These sources can be used to evaluate decisions for many situations.

- Utilitarianism says the most ethical action is the one that provides the greatest amount of good for the largest number of people — or, in more dire circumstances, the least amount of harm. This idea will be familiar to science fiction fans: At a critical moment in Star Trek II, Spock says “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”

- The rights approach dictates that the best decision is the one that preserves and protects human dignity and moral rights. People “have a right to be treated as ends, and not merely as means to other ends.”

- The fairness or justice approach says that all humans should be treated equally. If it’s not feasible to treat everyone equally, then there must be a standard of fairness that applies to everyone.

- The common good approach says that actions should promote to public life. This approach is used to advocate for laws and public services that appeal to the welfare of all.

- The virtue approach is based on characteristics such as compassion and honesty. With this approach, decision makers should ask things like “What kind of person would I be if I take this action?”

Once you have a firm understanding of these five sources, there is a clear set of progressive steps to consider in making an ethical decision:

- Recognize that an issue is indeed an ethical issue.

- Get all the facts regarding the issue.

- Evaluate all the alternative actions. With the utilitarian approach, look at which alternative will do the most good and the least harm. With the rights approach, think about which alternative preserves the rights of all stakeholders. With the justice approach, look at which option treats people most fairly. With the common good approach, consider the alternatives that serve the entire community. With the virtue approach, think about your own personal beliefs.

- Make your decision. If it still makes you uneasy, reconsider all the sources and see if you arrive at a different decision.

- Act on the decision.

Ask yourself, “What have I learned from this experience?” This reflection will help you make ethical decisions in the future.

The Issue-Contingent Model of Ethical Decision Making

In 1991, Thomas M. Jones, a professor at the University of Washington, criticized many of the existing models of ethical decision making at the time. He devised a new model that improved on previous efforts by introducing a variable called moral intensity and basing his research on social psychology.

Moral intensity takes into account several components: magnitude of consequences, social consensus, probability of effect, temporal immediacy and concentration of effect. Jones writes that two people, faced with the same ethical decision, might rightly come to different decisions because of these components. In effect, not all decisions are the same — a company introducing a dangerous new project has greater moral intensity than a decision to leave someone’s name off a group project. Both are unethical decisions, but one has a greater impact than the other.

In Jones’ model, decisions have four steps:

- Recognize issue

- Make judgment

- Establish moral intent

- Engage in behavior

All the dimensions of moral intensity must be considered at every step in the process, as well as organizational influences on decision making: group dynamics, authority structures and idea socialization. Decision makers must also be able to recognize their own biases when it comes to gauging moral intensity.

While the Issue-Contingent Model is old and somewhat complex, it’s a useful alternative for decision makers facing an ethical quandary in adaptable situations.